Superior antifouling coating scheme design

Carl Barnes, Head of Marine Consultancy ̶ Safinah explains the need to consider speed, activity and seawater temperature when designing an antifouling coating scheme.

Antifouling coatings comprise a soluble or partly soluble resin system that contains a mixture of biocides effective against a broad range of fouling organisms. These coatings primarily differ by the resin system used, often referred to as the ‘delivery mechanism’, and the type and level of biocide(s) used. The solubility of the resin system and the efficacy of the biocides used are the key parameters in determining the overall efficiency of the coating. Simply put, the resin system ‘polishes away’ in service, delivering the biocides to prevent fouling settlement.

Antifouling coatings currently make up around 80-90% of the fouling control market for marine shipping, with the remainder of the market comprising non-polishing foul release (both biocide-containing and biocide-free), along with hard ‘scrubbable’ coatings and a biocide-free polishing system.

Antifouling coating scheme selection

The selection of an antifouling coating scheme is clearly a complex task with over 140 products to choose from, which is further complicated as a scheme then needs to be designed that is specifically tailored to the expected ship-specific operational and environmental factors.

When designing an antifouling coating scheme, the dry film thickness (DFT) required is directly related to the expected vessel speed, activity and seawater temperature, along with the intended in-service period, i.e. 36 months, 60 months etc. In simplistic terms, the required DFT of an antifouling coating increases with increasing speed, activity, seawater temperature and longer in-service periods.

If the vessel eventually trades at speeds and/or activities and/or seawater temperatures significantly lower than the antifouling scheme design, the following are the likely consequences:

- Antifouling will have been applied in excess of what is required for the scheme life, which is a waste of upfront paint costs

- At the following dry dock there will be a significant DFT of antifouling remaining on the hull, which may cause problems with excess thickness build-up and subsequently cracking and delamination/detachment of the hull coatings. This can manifest itself as the coating dries out on entering the dry dock.

Antifouling issue

However, if the vessel trades at speeds and/or activity and/or seawater temperatures significantly higher than the antifouling scheme design, the antifouling coating is likely to ‘polish through’ prematurely before the end of the designed in-service period. Polish-through of the antifouling coating will expose the tie coat which will not provide any fouling protection, hence the tie coat will quickly foul even if the vessel is static for only a few days under normal port operations.

Figure 1 shows a striped pattern of non-fouled coating/fouled coating. The non-fouled areas are in way of spray overlap areas where additional antifouling paint has been applied. However, the areas between the overlaps have polished back to the tie coat and, as a result, have fouled.

Figure 1: Striped pattern of non-fouled coating/fouled coating

To understand how much of a problem premature polish-through of the antifouling coatings is on marine vessels, you need to look at data. Safinah, an independent coating consultancy, has a unique in-house database of coating condition assessments documented from dry dock supervision activities dating back to 2010.

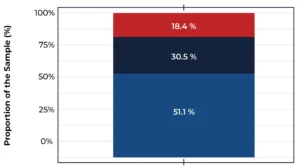

Safinah’s data from dry dock hull projects conducted between 2015-2024 showed that around 50% of the ships had a level of polish-through of the antifouling on arrival at dry dock, including around 30% of the ships with up to 20% polish-through and about 18% of ships with more than 20% polish-through (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Observed polish-through levels

Red = More than 20% polish-through

Dark Blue = Up to 20% polish-through

Lighter Blue = No polish-through

The data shows that premature polish-through of the antifouling coating is clearly a significant problem, and the accumulation of biofouling on areas of polish-through will lead to the following key industry issues:

- An increase in underwater hull roughness (from fouling species), which has a direct impact on fuel consumption and consequently the emission of air pollutants (greenhouse gases) which the IMO has adopted regulations to address

- An increased risk of translocating non-native, potentially invasive aquatic species.

Increased fuel consumption

However, the most significant financial penalty for the shipping industry is the increase in fuel consumption (whilst maintaining a constant speed) due to the adverse effects of hull fouling on the hydrodynamic performance of the vessel.

As such, the expected parameters for speed, activity and seawater temperature need to be carefully considered when designing the antifouling coating scheme. Typically, this is done using the vessel’s historical Automatic Identification System (AIS) data for the in-service period since the last dry dock, which is then analysed to obtain the required parameters. However, this historical data is only useful if the vessel is going to continue the same trade after the upcoming dry dock, and any predicted changes need to be carefully considered and taken into account.

Whilst the vessel speed can be relatively easy to predict (for example, charter party agreements typically state expected speeds and a ship’s activity will generally remain within an expected range), predicting the expected seawater temperature over a three- or five-year scheme life is a significant challenge.

The polishing rate of all antifouling technologies is affected by seawater temperature and whilst a faster polishing rate, and hence an increased rate of biocide delivery in high fouling challenge warmer waters, can be a positive, it makes calculating the correct antifouling coating scheme DFT more critical.

Safinah’s findings

Based on Safinah’s knowledge of antifouling coating schemes, a significant change in scheme thickness (DFT applied) can be seen for what appear as relatively minor changes to the seawater temperature. For example, moving from 25°C to 28°C, a relatively small increase of 3°C, the scheme DFT required significantly increasing by around 70µm (an approximate 30% increase in the total DFT required).

Therefore, assuming a linear polishing rate for simplicity, a vessel applied with a five-year scheme (for a seawater temperature of 25°C) which spends a high proportion of actual in-service operations at a temperature of 28°C, could expect to see significant areas of polish-through of the antifouling a year before the next scheduled dry dock. These areas of polish-through would quickly foul, with a subsequent increase in fuel consumption (when maintaining speed) and greenhouse gas emissions as well as significantly higher future dry dock costs. These could include increased cleaning and blasting costs and/or increased paint costs, as exposed tie coats cannot be directly overcoated with new antifouling.

To further add to the complexity, from analysis of antifouling coating schemes and in-service performance results from the dry dock database, Safinah has found that simply using average seawater temperatures is not accurate enough and a more in-depth analysis of the raw temperature data is required.

By analysing the condition of the hulls at dry dock and the antifouling coating scheme applied, Safinah has developed a method to incorporate other factors into the seawater temperature calculation which provides a ‘functional seawater temperature’ more fitting to the conditions expected to be encountered by the vessel.

Check out more articles like this in the latest issue of Protective Coatings Expert